Tohono O’odham people have relied on the Sonoran desert (in what is now southern Arizona and northern Mexico),as a food source for eons. This has included harvesting wild foods– like cholla buds, saguaro cactus fruit, mesquite bean pods, prickly pear, and acorns. In addition, during the summer months O’odham people practiced Akchin (dry land) farming, utilizing monsoon rains to grow hardy varieties of tepary beans, 60 day corn, and O’odham squash which they adapted ovr generations to the arid environment. Tohono O’odham (TO) people practiced this traditional form of farming and wild food collection to acquire a majority of their food until the mid 20th century. Federal work programs, boarding schools, and military service took people away from their homes and fields, and commodity food programs decreased people’s reliance on their environment and increased their dependence on federal resources. Increased enforcement of the US/Mexico border, which split the O’odham nation after the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, has also made traditional gathering of cultural materials more difficult. Water disputes hampered farming, as the Bureau of Indian Affairs and City of Tucson diverted water away from the tribe for their own projects. In 1983 the Southern Arizona Water Rights Settlement Act restored access to water for O’odham people, but farming had essentially dried up on the TO reservation. Tohono O’odham Community Action (TOCA) has been working since 1996 to try to restore traditional food traditions to their community.

TOCA’s origins reach back over two decades, with basket weaving classes for youth at Terrol Dew Johnson’s house. Terrol was conducting these classes in order to provide youth with a safe space, and to pass along traditional skills that had been taught to him by his grandmother and other elders. Basket classes expanded to gardens dedicated to producing and learning about the materials required to make baskets, as well as traditional foods. Terrol also turned to his grandmother to help lead bahidaj camps (described below), and cholla bud and mesquite harvests for the youth. TOCA co-founder Tristan Reader moved to Sells AZ, the TO Nation capital, when his wife got a job there. Tristan was an avid gardener, and he and Terrol became friends. Tristan taught him about the nonprofit world, and how to acquire grants to fund some of the work he had been doing. Between the two of them, and then the many staff, volunteers and community members who began to work with them, TOCA was born.

TOCA co-founders Terrol and Tristan, who have been working together for 20 years to bring healthy food and cultural programming to the TO community. Photo by Angelo Baca

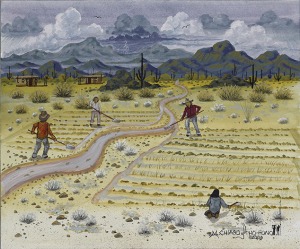

In addition to teaching basketry, TOCA’s goal was to rebuild the Tohono O’odham food system, through a revival of traditional farming and gathering. In 2002, TOCA founded the Alexander Pancho Memorial Learning Farm, on land that had been utilized by Terrol’s family. TOCA now grows traditional corn, beans, and squash on this land during the summer, and non-traditional crops like leafy greens during the winter months. TOCA also began to revive gathering camps, and encourage community members to gather traditional foods, which they then buy to sell in the TOCA gallery, in the Desert Rain Cafe, and on their website.

Anthony Franciso at the Alexander Poncho Memorial Learning Farm, December 2013. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

The current health crisis in Indian country is evident in the TO community, which has become well known to public health professionals for its rampant rates of diabetes. Traditional O’odham foods, such as tepary beans, mesquite beans, and cholla buds, are high in soluble fibers and inulin and help regulate blood sugar, slowing sugar absorption and improving insulin sensitivity. TOCA has been working to increase community access to traditional foods to help improve health, as well as maintain the culture and ceremonies around food gathering and production.

I had the opportunity to first visit TOCA in December 2013 when I was in Arizona for a basketry and traditional foods conference hosted by TOCA and the Native American Culinary Association. TOCA staff gave us a tour the farm as well as the school gardens (where I got to thresh beans!), and the cafe where we were served modern twists on delicious traditional foods, like prickly pear glazed pork chops, tepary bean hummus, squash enchiladas, lamb stew, and cholla bud salsa. At the invitation of TOCA Program Coordinator Cissimarie Juan, Angelo and I returned at the end of June 2014 for the annual TOCA bahidaj camp, where we spent the weekend camping in the desert, picking saguaro fruit, and rendering it into sitol (syrup), jam, and seeds.

Saguaro cacti, ha:san in the O’odham language, are found only in the Sonoran desert, can reach 50 feet and live up to 150 years. They grow on the south slope of hills, and first blossom when they are 50-70 years old. The fruits ripen in late May through June, and are ready to harvest when the green fruits start to turn pink.

According to O’odham tradition, the origin story of the saguaro begins with a little girl wandering through the desert, left to fend for herself while her mother traveled to play toka (a game similar to field hockey). As the girl looked for mother, animals like the coyote, quail, and eagle helped her. She finally found her mother, who yelled at her, causing her to run away crying. As her tears fell, she sank into the ground with her arms above her head. People pulled on them trying to extract her from the ground, but they were unable. Where the girl sank into the ground, a cactus grew, which now feeds people and wildlife with its fruit.

Harvesting bahidaj with a ku’ipad (harvesting stick). The kui’pad can be up to 20 feet long, and take skill and strength to maneuver. Photo by Angelo Baca

The fruits, or bahidaj, are harvested by assembling a ku’ipad (a harvest stick made by wiring 6-8’ long cactus ribs together, with a greasewood crosspiece at the top), and using this tool to jostle the ripe fruit free. People try to catch the falling fruits in buckets, or retrieve them from the ground. The bright red fruit filled with tiny black seeds (about 2,000 per fruit) are plucked from the thick green skin, and the empty skin is placed with the red center facing the sky, to call for the clouds that bring the monsoon rains. We were told not to worry if the fruit we placed in the bucket had stones or ants—these were filtered out after the fruit boiled, and the ants were supposed to add a nice mineral flavor. Jun, or sun-dried fruit that had already fallen from the cactus were also collected, and these fruits added a sweet caramel flavor to the brighter flavor of the fresh fruit.

The fruits can be eaten raw, or sundried, or processed into syrup or jam. Saguaro cactus fruit is rich in soluble fiber, vitamin C, protein and fat, and helps regulate if not reduce blood sugar levels if eaten fresh. The fruit may also help reduce cholesterol, which can contribute to other health problems like obesity, heart disease and high blood pressure.

Pouring bahidaj into the communal bucket, which will be taken back to camp and boiled down into syrup. Photo by Angelo Baca

We set out several time in teams to harvest the fruit, and then reconvened to pour all of the bahidaj into one big bucket, to which just enough water to cover the fruit was added. This was allowed to sit for a few hours. The mixture was then brought to a boil in a large pot over the stove, and cooked until the fruit was all broken up. As the fruit boiled, TOCA staff member Mike Enis explained that the clouds like the smell of cooking bahidaj, and this would bring them around. Foam developed around the rim of the pot, a visual representation of the clouds that will be gathering. The fruit was then strained with a sieve for some batches, a bluebird flour bag for others, to separate the seeds and pulp (and ants and rocks) from the juice. The strained juice was then placed back on the fire and cooked until it became thick and syrupy. The final product was the consistency of maple syrup. The syrup was then placed in small jam jars, to be taken home by camp participants. The syrup can be drizzled on meats, salads or pancakes, or used to sweeten beverages, and is considered a healthier sweetener, as saguaro syrup won’t spike blood sugar the way refined sugars will.

Boiling bahidaj. The foam gathering on the surface represents the clouds that will hopefully come at the end of the harvest. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

The pulp and seeds were spread onto a tarp to dry in the hot sun. As the pulp dried, people would periodically take up flat sticks and beat it, to help separate out the seeds. After the pulp mixture was mostly dried, it was sorted through by hand, separating seeds, pulp, rocks and thorns. The seeds were placed in bags to be brought home to add to cookies, breads, salads and smoothies. Traditionally the seeds were also ground as a nut butter, as they contain a vital source of protein, fiber and healthy fats.

We also had the opportunity to see jam made the traditional way, an activity rarely practiced because of its time consuming nature. TOCA staff took a pot full of sitol (syrup), mixed in the pulp that had been painstakingly separated from the seeds, and stirred for hours. They used a paloverde branch to stir the mixture, and to fish out any stray seeds, thorns, or sticks. We also had the opportunity to bring home some of this precious food.

Paloverde branches were used to stir the jam, and catch any stray seeds or sticks. Photo by Angelo Baca

The bahidaj camp gave community members, especially youth, the opportunity to come together, learn songs, and partake in this rare food. Terrol and Tristan commented proudly that youth who had been part of TOCA for years were there functioning as leaders, teaching songs and jam making, and leading teams of bahidaj pickers. TOCA also has Food Corp interns, Rebecca and Julia, who have worked tirelessly in the school gardens, and who led games and activities at the camp.

After a long weekend of hosting the bahidaj camp, most TOCA staff had the following Monday off. Except for Jesse, a coordinator for Project Oidag, which tends to gardens around the community and hosts workshops for high school students. We found Jesse watering their garden behind the IHS clinic (although here, as in other communities we visited, the produce can’t actually enter the hospital). Project Oidag is a collective of O’odham Youth who came together in the summer of 2011 under the New Generation of O’odham Farmers Youth Internship Program. When the internship ended, the youth continued the project on their own, growing produce to sell and educating other students.

Currently, TOCA is also working with local schools to improve the breakfast and lunch programs to include healthier more culturally appropriate foods. To do this, they are developing a food service social enterprise, beginning farmer training programs, and farm-to-school programs. As Tristan described, they are working to develop a full food system. He noted that TO is one of the poorest reservations in the United States, but there is still between $50 and $70 million a year spent on food, and of that less than 1% is probably being captured locally. TOCA is working on improving this system to benefit the health, culture and local economy of the TO Nation.

4 comments ›