Even prior to the strain put on the food economy by the COVID-19 pandemic, Native American communities have been fighting food insecurity. One quarter of American Indian/Alaska Native households receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, 276 tribal nations administer the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), 68% of AI/AN children qualify for free lunches, and AI/ANs make up more than 12% of the participants in the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutrition program.[1] The sudden loss of jobs, shutdown of programs, and empty grocery store shelves have placed into stark relief the importance of many food sovereignty projects that tribes have been working to implement, as well as the creative ways that Native people have been working to utilize federal programs, and have resulted in a doubling down of efforts on the part of many grassroots programs devoted to traditional foods.

One federal program that tribal representatives have worked hard to try to adapt the needs of tribal communities is the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservation (FDPIR), created in 1977 to provide access to food for low-income Native American households that did not have easy access to grocery stores to fully utilize SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program). There are approximately 276 tribes receiving benefits under FDPIR through 102 Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs) and 3 State agencies. The program serves approximately 90,200 participants on an average monthly basis.[2] One in ten participants have zero income and 1/3 don’t have access to a vehicle. At a time when many Americans are ordering their groceries through Peapod, Instacart, or Amazon, 59% of FDPIR users do not have access to internet.[3]

This program has seen an increase in use since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (an average of between 11-50% increase in new participants in addition to the people who have historically participated in the program), and the numbers are expected to continue to rise as people lose employment. 80% of the sites have also reported increases in clients taking the full amount of food offered, at the same time that challenges with food supply chains have made stocking facilities more difficult. [4] Adapting to social distancing regulations—which might include packaging up food for curb side pick-up, or delivering to vulnerable participants- as well as placing additional delivery orders to try to meet need, also costs additional money.[5] The third bill of the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) designates $100 million for FDPIR for additional food purchases and facility improvements. But what the Native Farm Bill Coalition has been lobbying for is for the ability of tribes to exercise self-governance authority, including around the sourcing of foods, to improve responsiveness to the crisis.[6]

This push for tribal self-governing authority over the contents of food boxes has been an ongoing fight. For most of the history of the FDPIR program, the content of the food boxes that each Native American family received through this program was comprised of high carb, high sodium, processed commodity surplus foods—foods that have contributed to the disproportionately high rates of diabetes. In recent years, the FDPIR Food Package Review Work Group has been working hard to improve the nutritional quality of this program and to distribute the food in a way that is more conducive to giving families choices.[7]

NAFDPIR’s past National President and current Midwest Region President, Joe VanAlstine, who is from the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawak in Michigan, described the successful efforts of this working group to reduce the amount of sodium in canned foods, improve labeling, and increase the offerings of fresh foods and traditional foods. Participants now receive hand-harvested wild rice, blue cornmeal, grass-fed bison, frozen fresh wild-caught salmon, as well as more fresh produce. But because the program is administered by USDA, all of the food boxes for every participant across the country had to contain the same ingredients, despite the fact that quantities of traditional foods are limited, and many community members would rather receive a greater amount of their own traditional foods rather than a taste of foods from around the country. After much lobbying by tribal representatives, including the Native Farm Bill Coalition, the 2018 Farm Bill (passed in December 20, 2018) included provisions for $5million to be made available for demonstration projects in self-determined contracts (known as 638 contracts in reference to Public Law 93-638) for ITOs that are administering FDPIR to purchase local foods (of similar or higher nutritional value than the food it is supplanting in the existing FDPIR food package) for their participants.[8]

photos I took of the Ziibimijwang farm in 2019

The sudden limiting of supply chains, coupled with the struggles of small local farmers has increased the urgency with which ITOs and Native advocates are pushing for 638 authority to be able to source locally grown food to feed their constituents. Van Alstine and others have been pushing for years for tribes to be able to locally source foods for FDPIR packages. In addition to running his local FDPIR office, Van Alstine also chairs Ziibimijwang Inc., a tribally chartered cooperation that oversees Ziibimijwang farm, a 100 acre farm owned by the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawak that is about to start its sixth growing season. As the farm’s website describes, “The purpose of the 100 acre farm will enhance LTBB food sovereignty by providing a reliable food source for the community independent of the larger food system, encouraging a healthy lifestyle for our people and enhancing people’s knowledge and ability to do farming/gardening and subsistence activities for themselves.”[9] The farm had a great season last year, marketing their food products at the tribally run Minogan Market in Mackinaw City, as well as to pow wows, farmers markets, restaurants, and the tribal casino. They were getting ready to expand sales this year when all of these markets suddenly closed. So while in one job Van Alstine is struggling to source fresh fruits and vegetables for the 200 families he serves, in his other position he’s struggling to find a market for the produce from the tribe’s farm. What would make the most sense, he argues, is to connect the FDPIR food distribution site and the farm, using USDA funds to help keep this and other local farms going. This is not currently possible, but this is the type of shift that could become possible with an implementation of 638 authority. In the meantime, Ziibimijwang has started a small TSA (Tribally Supported Agriculture) program, selling boxes of food produced on the farm to local consumers, as well as selling other products like maple sugar online.[10]

In addition to connecting the FDPIR program to the farm, Van Alstine is working to create a department of agriculture for his tribal government, and hopes that all of the panic around food right now will drive home the point to his tribal government that this is needed. He proclaims, “If we can’t feed our own people, how can we truly call ourselves sovereign? ?” Since the tribal casino is shut down for now, he hopes that now the community will see the farm as a different kind of economic engine. [11]

On a national level, Joe wants to get other food distribution directors to understand “they’re more than just handing out food; this program can expand itself a lot more, and not just be a conduit for food to be taken out.” At a food sovereignty summit last year, Joe was pleased to see two FDPIR directors taking part in the activities. “This is what all of the directors need to be doing.” He feels that some of the directors closer to retirement are not ready to let go of the old model, but some of the newer directors are more open minded about expanding their operations to include growing operations and a greater focus on food sovereignty. “I’m grateful to my tribal government for the opportunity to serve our tribal citizens as the Food Distribution Director. This position has taught me how to be innovative with the ways in which I can provide for my people though food. Moreover, this position has provided me with an area to advocate for our sovereignty as a Native sovereign nation. I once had an elder asked me, ‘Joe, are you trying to work yourself out of a job?’ And I said yes I am. I want to provide food sovereignty for my tribal nation.” His ultimate dream is someday eliminating the need for FDPIR entirely: “if the tribe can do it for themselves, why have the government do it for us?” In the meantime, he’s hoping to use some of the new infrastructure money available from COVID relief funding to get new buildings and freezers. As he described, “Tribes need to take FDPIR and make it our own; build around it and build on it”

Overall tribal communities and advocates are lobbying for greater amount of local control over the programs that feed their communities. As members of the Native Farm Bill Coalition have described, “Indian Country needs a consistent, comprehensive, and tribal-led approach to tailor federal food assistance programs to the specific needs of tribal communities and citizens.” This would require FDPIR purchasing and distribution to occur on a regional basis and include as much locally and regionally tribal-produced food as reasonably possible.[12]

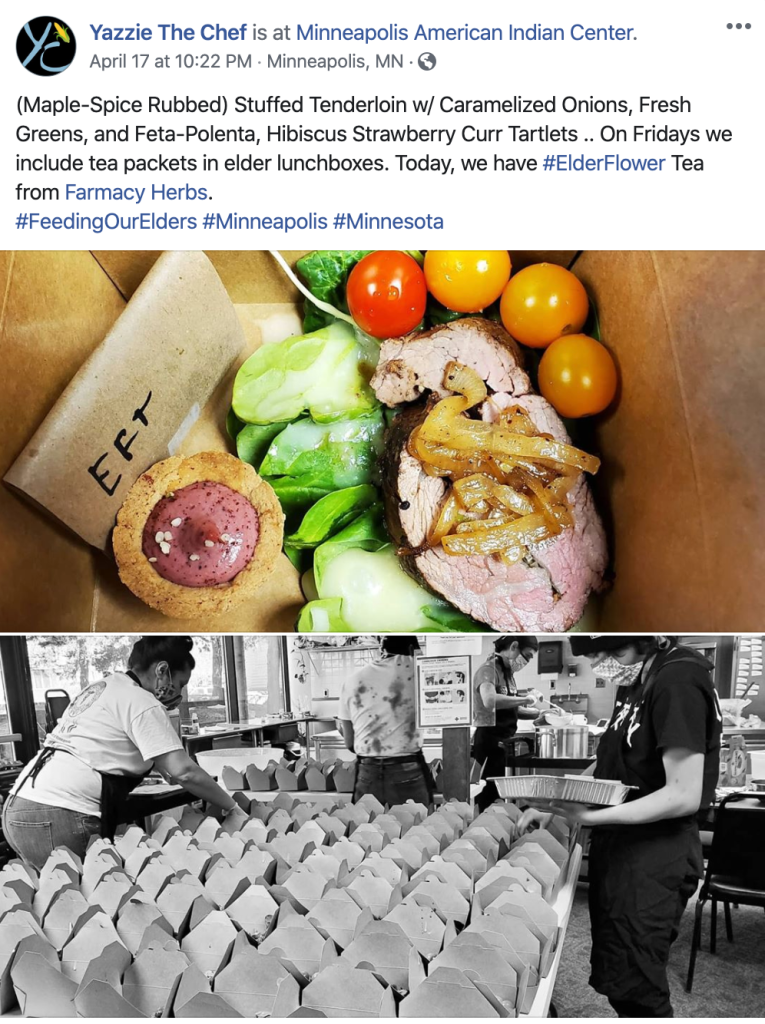

On another level, Native community members are working hard on the grassroots level to step in to fill the void left by canceled feeding programs that impacted the most food-insecure members of society—elders and youth. In Minneapolis, the American Indian Center had provided lunch for elders every week day afternoon, a program that was canceled with the onset of social distancing recommendations out of concern for the health of this vulnerable population. The Center’s Gatherings Café also closed to the public at the same time. In addition, local Native chef Brian Yazzie (Navajo) found himself without any of the catering and educational programming jobs that he was accustomed to. Brian partnered with Ben Shendo (Pueblo) and Linus Yellowhorse (Tohono O’odham) in the café, along with other community volunteers like baker Vanessa Casillas (Hochunk) to put together meals for the elders, using supplies in the café as well as goods donated by food producers and restaurants across the state and donations from across the country. This ad hoc crew prepares about a hundred meals a day for elders, focusing on as many healthy traditional foods as they are able, which are then delivered across the Twin Cities.[13]

In addition to running his own catering operation, Brian served as a chef at the main kitchen at the Oceti Sakowin camp at Standing Rock in 2016, and he recently reflected on how cooking healthy meals for 2500-4000 people a day helped to prepare him for this work. And similar to his work in the kitchen at Standing Rock, as much as they would like to plan a menu for the week, the daily meals require flexibility and creativity, as surprise donations come in on the daily. Brian and his ad hoc crew have committed to continue providing meals for the elders until they are allowed to return to the Center.[14]

canned goods for sale in the CYRP gift shop, 2014

Julie in the Keya Cafe Kitchen during my visit in 2014

Youth picking onions in the CYRP garden, 2014

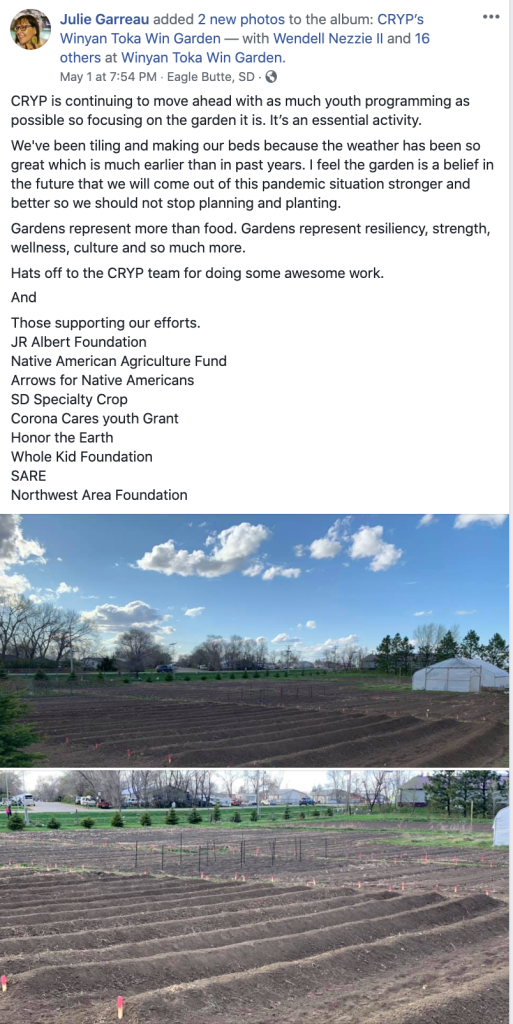

Programs have also had to come up with creative ways to keep youth fed. I spoke to Julie Garreau at the Cheyenne River Youth Project (CRYP) on the Cheyenne River reservation in South Dakota. CYRP has been providing services for youth in the community, including making sure they have access to sufficient healthy food, for the past 30 years. Generally the youth would receive breakfast and lunch in school, and then come to the Main (the CRYP youth center) for snacks and dinner. Now with schools closed, Julie recognizes that she may be providing the only solid meal that some kids are getting each day— which has grown from an average of 25-30 kids a day to 50. The Main has had to dramatically shift its activities, with employees working far apart from each other, and buying more packaged food that they won’t need to touch. Julie described how CYRP has been working on and thinking about food security and food sovereignty for a long time— they have a garden alongside the center where they grow produce in the summer that they sell and give away through their little farmers market, and which they can and dry to keep in their cafe and gift shops. They are now turning to these stores, but recognize that they cannot feed the whole reservation this way. Even so, despite the fact that their programming is geared towards youth ages 4-18, when the occasional mother has come in expressing distress about not having food at home, Julie has sent her away with packages of food. When I asked her what kind of lessons we can take away from this experience, she paused for a moment and reflected, “I hear a lot of people saying they can’t wait for things to go back to normal. We don’t want normal…I hope to hell nothing goes back to the way it was before, we need better.” Her hope is that the tribal leadership comes out of this experience really thinking hard about food systems on the reservation and how to better support projects like gardens that will help to make families more food secure. She has faith that her community will pull through: the tribe shut down its borders to outsiders and hired tribal members to serve as border agents, and she knows her community is resilient. “We are resilient people anyway, but I don’t think the systems are resilient. That’s the situation. We have proven we can make it through a lot but the systems we have created are not resilient.” The goal now is to create more resilient systems. Julie also recommends that in funding recover efforts that funders look not only to the short term, but also the midterm and the long term. To prevent things from going “back to the way it was before, because we need better.”[15] You can help support CRYP here.

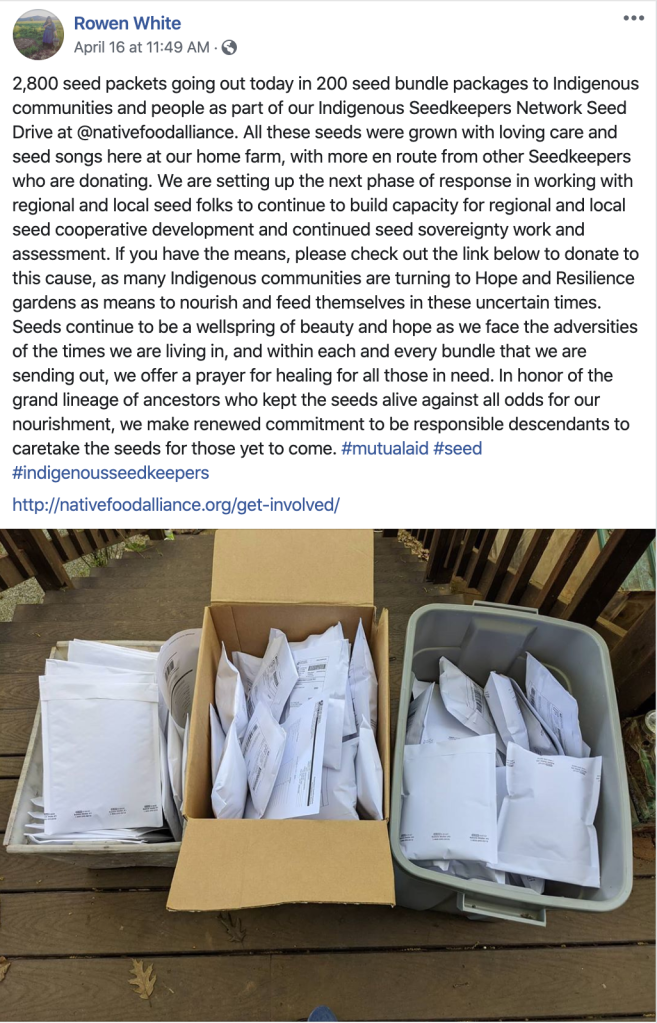

One way people responded to concerns about disruptions to a global food chain was to rush out to buy seeds to plant this generation’s version of the victory garden. “Resilience gardens” as Rowen White, director of the Indigenous Seedkeepers Network calls them. Rowen, who is well known for the suitcase of seeds that she brings to every food summit and the innumerable seed keeping workshops she has hosted in tribal communities across the country, put an offer out on Facebook to send seeds to Native families who needed them. She received over 700 responses, and has been working long hours with her children to create the “three sisters and friends” seed packages to mail out. There are 14 varieties in each bundle, including herbs and fast growing varieties like radishes and salad greens, as well as a few flowers to help the pollinator habitat and provide beauty. Rowen is also developing and collating educational materials and a series of webinars. The hope is that some of the recipients of these bundles will be awakened to the importance of growing their own food, and stewarding their own seed collections. Other seed keepers have similarly being inundated with requests for seeds.[16] This sudden explosion of need, and the fact that seed companies haven’t been able to keep up with demand, highlights the importance of ISKN’s work; while it took a pandemic to finally pique people’s interests in growing their own food, members of ISKN are grateful that their message is finally taking hold. As Beth Roach (Nottoway) of the Alliance of Native Seedkeepers based in Richmond Virginia described, “Every seed we send out, we send love with it. We are grateful for people to be part of system.” Rowen describes this whole adaptive process as a reinvigorating of the traditional trade routes that kept tribes supplied for eons.[17]

But this sudden turn to focus on providing food for community members to make up for the shortfalls in grocery stores has also shifted, even if temporarily, the mission of some tribal seed and garden programs. One community has been working for years to grow out and rematriate (send back to their original communities) a huge collection of Indigenous heirloom seed varieties. Some of that work has been put on hold as the farm crew works on distributing food to those in need and planting market crops for the upcoming season. Linda Black Elk, director of food sovereignty programs at United Tribes Technical College in North Dakota, described discussions in her program regarding how the focus in the coming season is going to shift away from research and into primarily food production. Others on a recent ISKN call, ranging from Ottawa and Saskatchewan down to New Mexico, also described a planned divergence from focusing on rare seeds to focusing on food crops.[18]

Their short term vision is to get as many seeds as possible out to interested gardeners and get as much food as possible planted. The long term vision is to support more community based seed keepers, create new seed keepers who aren’t reliant on seed companies for their seed stock, and to create regional seed hubs to coordinate these efforts on a more local scale.

Community-based food organizations are also continuing their work by taking their programming online. For the past four springs, the Great Lakes Intertribal Food Summit has brought together hundreds of people for hands on demonstrations, presentations, and knowledge and food exchange. In past years it was hosted on the Gun Lake Potawatomi reservation, the Meskwaki Settlement, and the Pokagan band reservation, with help from the host communities as well as the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and the Intertribal Agriculture Council. This year, due to concerns about travel and social distancing, the in person gathering has been canceled, but coordinators like Dan Cornelius (Oneida) have come together to attempt to move the gathering online. This year’s virtual summit will include livestreamed demonstrations of food procurement and preparation, as well as pre-recorded videos.

One of the beloved feature of the past summits was the culinary mentor program—opportunities for up and coming Native chefs to be partnered with more seasoned chefs for a mentoring and support experience. The chefs would collaborate to feed delicious traditional foods to the hundreds of conference participants, and would remain connected throughout the year as they planned community based cooking events. This year, because of the cancelation of in person gatherings, the culinary program, under the guidance of Ho-Chunk chef Elena Terry, is creating webinars to bring together indigenous chefs to learn from and support one another, and continue discussions around cooking. The hope is to help chefs, many of whom have suddenly found themselves without employment, to find purpose while they’re working in a different capacity.

kitchen crew at the food summit hosted at Mashantucket Pequot, 2018. photo by EH

kitchen crew, Great Lakes food summit hosted at Meskwaki, 2017. Photo by EH

The Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and other community based organizations like the I-Collective have also organized webinars focused on traditional foods and medicines for health, and the importance of foraging in a respectful and sustainable way, as many inexperienced gatherers have suddenly taken up an interest in foraging to fill time and replace fresh produce that might be missing from their grocery stores. This increased interest can prove disastrous for some plant varieties if overharvested, and will strain Indigenous community access to these foods.

While the internet has been a boon in creating community and bringing in donations to grassroots organizations, in some ways it has also contributed to the reasons Denisa Livingston (Diné) has been struggling to continue to find provisions for the elders her organization, Diné Community Advocacy Alliance (DCAA) serves. In a recent phone meeting of the Slow Food Turtle Island Association (Denisa serves as the Indigenous Councilor of the Global North for Slow Food International), she described how an article had come out about the benefits of Navajo tea (green thread), as well as others about how to order shelf stable foods online from Native run companies. Now the companies that she had relied on for the foodstuffs to fill the boxes for the elders are no longer available because media coverage caused the general public to seek out these foods. In frustration she proclaimed, “So do we just get frybread ingredients again and go back to survival foods?” DCAA has been working diligently to help Diné people with diabetes and heart disease stabilize their health through improved nutrition, and her concern is that now there is a shortage of healthy food and clean safe drinking water on Navajo Nation, people will have to turn to what’s available, which will only exacerbate these health conditions, and make it challenging to fight off the virus.[19] While the internet has opened new markets for tribal food producers, communities are seeking to find the balance between wanting financial success for these producers and ensuring those foods are still available for community members.

Denisa at Terra Madre in Turin, Italy in 2018. Photo by EH

Indigenous communities have been continuously working to try to provide sustenance to a largely food insecure population, work made more pressing by the COVID-19 pandemic. And the growing season is not contingent on functionality of programs or availability of funds. The cases here are just the tip of the iceberg of the ways that Native communities are working to ensure their members are fed. Luckily, there are grassroots organizations who were already working on these types of issues, who are now stepping up even harder to try to provide for in increasingly aware population. To contend with these challenges, and to push for a more resilient sustainable future, tribal communities are drawing on nation-wide resources to continue educational programming and create new meal programs, but are also pushing for the ability to better support local food systems, through tailoring federal feeding programs to their local context, and working to localize seed networks. As April Tarbell, who is working with multiple programs and institutions to keep her tribal community fed described, “It’s brought our people closer, at 6 feet apart.”

[1] National Congress American Indians Policy Update. 2019 Annual Convention, Albuquerque NM. “Agriculture and Nutrition” page 3. Available at http://www.ncai.org/attachments/PolicyPaper_zuufQisBiFmwncntutmICsEJXHWPReKwjpbpYsxALTXBECBsNDS_2019%20NCAI%20Annual%20Convention%20Policy%20Update.pdf

[2] Erin Parker, presenting during “COVID-19 Update and Impacts: Administrative and Legislative actions.” Native Farm Bill Coalition (NFBC) and Indigenous Food and Agriculture Initiative (IFAI) Webinar and Listening Session April 1 2020. https://indigenousfoodandag.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IFAI-NFBC-COVID19-UpdatesAndImpacts-04012020-Final.pdf?utm_source=Native+Farm+Bill+Coalition+Webinar+Registrants+4%2F1%2F20&utm_campaign=153d43387f-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_05_06_02_23_COPY_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d314a8114e-153d43387f-598582834

[3] Parker “COVID-10 Update”

[4] Parker “COVID-10 Update”

[5] Parker “COVID-10 Update”

[6] Colby Duren, presenting slide 21, “Covid-19 update and Impacts”

[7] https://www.fns.usda.gov/fdpir/fdpir-food-package-review-work-group; https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USFNS/bulletins/12e6f0e

[8]“Request for information: Self-Determination Demonstration Project for Tribes That Administer the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations.” A Notice by the Fod and Nutrition Service on 12/10/2019 in Federal Register

[9]Ziibimijwang Farm facebook site, “About” section https://www.facebook.com/pg/ZiibiFarm/about/?ref=page_internal

[10] Interview with Joe VanAlstine, April 2 2020.

[11] Interview with Joe VanAlstine, April 2 2020.

[12] https://seedsofnativehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Title-IV-Nutrition.pdf

[13] Personal communication with Brian Yazzie

[14] Brian Yazzie Facebook Live stream, April 16 2020.

[15] Interview with Julie Garreau April 4.2.20

[16] ISKN zoom meeting, April 1 2020

[17] ISKN zoom meeting, April 1 2020

[18] ISKN zoom meeting, April 1 2020

[19] Slow Food Turtle Island zoom meeting April 16, 2020

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I will

bookmark your blog and check again here regularly.

I’m quite certain I’ll learn many new stuff right here!

Good luck for the next!