According to Bad River tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins, “every Indian walking around in Bad River is an unbelievable food producing dynamo waiting to be unleashed.” In describing his community, Mike doesn’t focus on poverty or poor health (Bad River is among the top third areas in Indian country with the highest prevalence of diabetes, with more than half of the reservation’s population either has the disease or is showing early signs of it.) He focuses on the non-monetary wealth of the region, which he is determined to help tribal members tap into, through supporting a suite of food systems projects.

Native American communities in Wisconsin. Photo courtesy of the Tribal Libraries, Archives, and Museums Project.

The Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians (Chippewa, Ojibwe, and Anishnaabe are all different names for the same cultural group) is located on a 125,000 acre reservation in Northern Wisconsin, on the south shore of Lake Superior. As described in the post about White Earth, centuries ago Anishnaabe people migrated from the east, eventually forming the capital of the nation on Madeline Island in Lake Superior. The residents of Bad River are descendants of those Anishnaabe who remained at the capitol, while other bands pushed north and West. The treaty of 1854 set aside 200 acres on the island for the Bad River Band (then known as the Lapointe Band), as well as their current reservation on the south shore of Lake Superior. In addition the 1854 treaty set aside reservations for three other federal recognized Ojibwe bands, Red Cliff, Lac Du Flambeau, and Lac Courte Orielles (Mole Lake and St Croix are also federally recognized Ojibwe communities in Wisconsin, but didn’t receive land until 1937 and 1938). Originally called Mashkiiziibii, or Medicine River, according to our host Jeremy, the river was renamed Bad River by settlers because of the number of drownings that took place in the tricky currents. The area that is now the Bad River reservation was originally known as “Gete Gititaaning,” meaning “at the old garden.” While Anishnaabe people followed seasonal routes around their territory, in the spring they would plant their gardens in the rich soil of the river flood plain, and return to harvest in the fall.

Jeremy McClain, who served as the Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Program (FRTEP) Educator for the Bad River reservation from 2012-2014, standing near the Turtle Garden. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

One of the gardening projects working to feed the people of Bad River is operating in one of these ancient gardening sites. Others are helping set up gardens at the Elders center, helping residents establish home gardens, and experimenting with permaculture methods to grow more food in the heavy clay soil. The tribe is also working on re-educating members on how to harvest and prepare wild foods, and providing them with some of the resources to carry this out.

The Bad River Gitiganing Community Garden project was started in 2003 by Luis Salas who, along with several community members, ran the project for several years before taking another job. Two years ago, Jeremy McClain took on this site as part of his job as the Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Program (FRTEP) Educator for the Bad River reservation, funded through the USDA and run out of the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. The turtle-shaped garden once held mostly medicine plants, but has now been expanded to include lettuces, tomatoes, squash, cabbage, carrots, onions, beans, sunflowers, corn and other food crops. Adjacent to the turtle garden is a new orchard, containing dozens of apple trees, that was planted by 60 summer youth workers this past July 11. They didn’t want to disturb the ground because of the historic significance of the site, and so Jeremy imported 5 truck loads of soil, which was placed on top of the existing soil. The trees were planted in mounds of this new soil. Next summer they hope to expand with another 30 fruit trees, and to create permaculture garden beds in between the trees.

Gitiganing orchard. Repairing the hoop house in the background is one of the planned projects for next season. Photo by Angelo Baca

In addition to brining in soil for the orchard, the FRTEP program also did a soil giveaway, buying truck loads of rich, black soil and placing it in piles around the community for people to take back to their gardens. They also offered tilling services for home gardeners. Fifteen families took advantage of these services, increasing garden space on the reservation by about 1000 square feet, according to Jeremy. The FRTEP program also offered raised bed gardens, establishing beds at the Birch Hill Community House, the Boys and Girls Club center, and at the Elderly Center, as well as at 4 individual home plots. At each of the community sites, Jeremy engaged the youth with planting and harvesting activities, to encourage exercise and healthy eating as part of a youth obesity and diabetes prevention grant. As part of weekly programming, Jeremy meet with the youth and taught them about weeding, watering, different stages of the plant life, soil composition, and soil health. About 60 youth took part in these programs. Jeremy also coordinated with Dan Powless, Kathy Baerg, and other community members to do a community plant give away in April. In 2013 they propagated about 700 plants, expanding this past spring to 2000 plants, mostly peppers and tomatoes. The plants were started under grow lights at the community center and in Jeremy’s office, and then given away to home gardeners, and planted in the community raised beds.

Sandra Corbine examines the raised beds at the Elderly Center. They’ve had these gardens for 3 years. Elders stop by and take care of these gardens, and then the food goes towards an afternoon activity for the elders (like making salsa or learning about pressure cooking).The Bad River Revitalization Program grant also made it possible for Sandra to purchase Farmers Market Vouchers for elders that they can use to shop with local farmers (like Don’s berry patch and Bob the corn man), as well as the Ashland food co-op. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Kathy Baerg, who works at the Bad River Health and Wellness Center, has also helped elders have gardens at their homes, through a Community Transformation Grant out of the CDC, that was funneled to them through the Great Lakes Intertribal Council (GLITC). Through a Healthy Eating Active Living grant that focuses on decreasing commercial tobacco use as well as increasing vegetable intake, Kathy has helped elders set up two different types of gardens: traditional medicine gardens in raised beds, and straw bale gardens for vegetables. Kathy coordinated events last winter that focused on traditional storytelling that focused on the use of traditional tobacco. What came out of discussions around those events was that people needed greater access to traditional tobacco, which led to the traditional medicine garden project. Participants received raised beds, cedar trees, and tobacco, sweetgrass and sage plants.

Three Sisters garden, built by Jeremy’s program, which aims to bring youth and elders together to work in these gardens. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Example of a straw bale garden. Photo courtesy of Roots Simple

The idea for the straw bale gardens came to Kathy when she attended a GLITC conference in May 2013 and heard a presentation by Joel Karston, who had developed the idea for these gardens. On the way back from the conference Kathy and a friend picked up 4 straw bales and spent the summer trying the idea for themselves. At a winter health fair that year Kathy set up a table and collected names of those interested in straw bale gardens. This past summer 50 people tried the gardens, with varying rates of success. They received straw bales, hoses, fencing, tools and plants through Kathy’s grant. Between the traditional medicine gardens and the straw bale gardens, Kathy estimates over 100 elders took part in her project.

Josh, a worker at the Rainbow Garden project, examining the hugelkultur bed. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

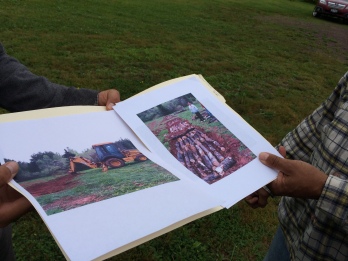

After visiting the Gitiganing project and the raised beds at the elders center, we headed out to the Rainbow Garden Project, where Dan Powless, Renewable Energy Coordinator and Food Sovereignty coordinator for the Bad River tribe is experimenting with hugelkultur, a permaculture method developed by Austrian farmer Sepp Holzer. Danny attended a few permaculture courses, and “found them like what Native people do,” working with the landscape and integrating available materials to grow food. In several places on the reservation, the heavy clay soil makes it difficult to grow most crops. So Danny and his crew decided to try hugelkultur, which entails digging a pit and filling it with logs (in their case logs from a local beaver pond), compost and soil until you’ve created a mound. The mound will settle as the logs and compost decompose, providing a nutrient source for the plants. Food from this garden is used in funerals and ceremonies, as well as youth and elderly programs.

Danny Powless shows us photos of the construction of the hugelkultur bed last year. Photo of the photos by Elizabeth Hoover

Hubbard squash growing in the hugelkultur bed. According to Danny, Hubbard squash is one of the elders’ favorites. Photo by Angelo Baca

There are also plans to increase the tribe’s food growing operations through a farm, about 20 miles from the reservation, which was donated to the tribe when the owner passed away. The land on the farm (which was 18-22 acres, depending on who was describing the farm to me) has been laying fallow for between 15-20 years. Danny is supervising two VISTA workers (who arrived at Bad River the day before we did.) Part of the duties of these workers will be to help the tribe to create a food sovereignty plan, and decide the best course of action for the farm.

In addition to promoting gardening in the community, another goal of people involved in food systems work at Bad River is to give tribal members the knowledge and resources necessary to harvest wild foods. Jeremy did this through a series of workshops for youth; during our visit we had the opportunity to sit in on workshops to teach kids how to make wild rice knockers (the sticks used to knock the kernels of wild rice from their stems), and how to navigate canoes to go pick the rice. Jeremy described how it was his goal to help the youth access the rice for health and wellness reasons, as well as providing an economic opportunity for families from selling rice.

On the morning of August 18, Jeremy gathered a dozen or so children around, and after discussing the role of wild rice in the Ojibwe migration story, as well as potential threats to rice (like water pollution from mining), everyone set to work with hand held planers to turn blocks of cedar into rice knockers.

Russ Denomie, Christian Delgado, Brennan Corbine, and Quintin Taylor and Justice Ford turning chunks of cedar into rice knockers using hand planes. Photo by Angelo Baca

The next morning they headed out to the boat launch by the tribal fish hatchery–each year the tribal Natural Resources Department nets walleyes, hatches the eggs and returns many millions of fry and fingerlings to the Kakagon and Bad Rivers. There they jumped in boats to tour the Kakagon Slough, home to the largest natural rice beds in the Great Lakes Basin.

Bird’s eye view of the Kakagon- Bad River Slough. Photo courtesy of Jim Meeker via the Bad River tribal website

Upon returning to the docks, the kids spent the afternoon learning how to paddle a canoe, how to use a long pole to maneuver a canoe, and for the person sitting in the front of the canoe how to use their knockers to bend the grass and tap the rice into the bottom of the canoe. They also learned how to fall out of a canoe without dumping all of their rice, and how to right a canoe once it had been flipped over.

Brennan Corbine going for a swim in the Kakagon (despite cold, cloudy weather and leaches). Photo by Angelo Baca

Tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins spoke to us about how a relationship with the environment and traditional food systems is imperative for understanding Ojibwe language and culture, and vice versa. He described what he thought of as synapses no longer firing in the brains of tribal members who weren’t taking part in traditional food activities. To remedy this, he has been supporting food initiative projects on the reservation as much as possible. When a needs assessment around traditional harvesting activities was done in the community, they found that one of the biggest barriers to access was a lack of equipment. To increase access to maple harvesting, Mike had the tribe buy two evaporators, and sap sacks and sap sack holders for interested families. The way Mike sees it, “That stove and pan wasn’t just a boiler stove and pan anymore. It became a portal of access that allowed our people to pass through it out into the natural world and come back with beautiful sweet water, fire it up, boil it down and make food for themselves. That still became this portal of access that had power and spirit in it.” Jeremy followed this with his youth seasonal harvesting program through FRTEP, to involve all ages in becoming interested in maple syrup production.

Madeline Island, described by some realtors as “the Caribbean of the north.” Photo courtesy of Aaron C Jors

Another “portal of access” that Mike described is the Sprit Runner, a 25 food Mako boat with a 250 horsepower Mercury outboard motor that the tribe now owns, and is working to fix up. His dream is for tribal members to be able to take that boat fishing on Lake Superior, to be out there among the wealthy tourists, gathering food. In addition to gathering resources to get out on the lake, the Bad River tribe is also working to get some of its lake-side land back. The Tribe just rejected the renewal of a 50 year lease for the north tip of Madeline Island, a site with eight condos that had been paying $90,000 a year in rent. After 2017, that land will go back to the Bad River tribe. It was also recently discovered that some of the cabins owned by wealthy vacationers on Oak Point, on the south shore of Lake Superior, are also on land technically owned by the Bad River tribe, and they have been served eviction notices, according to the tribal chairman. Years ago, Ojibwe had fall rice camps on Oak Point, where wild rice was brought in from the sloughs, parched and winnowed. Mike described, “one of my most ferocious and gentle dreams is that 50 years from now, an Anishinaabe stands at the mouth of Bad River looking west over through the sloughs and Oak Point and sees linear columns of smoke from traditional rice camps. And for that to happen, there is got to be a little ferocity because there is folks there that feel ownership now because of how long we’ve been disconnected, but those synapse firings are just waiting for that little bit of electricity of fire throwing them.” Referring to the kids who had been attending two days of ricing workshops, he continued; “Those little ones we’re seeing today are going to be that current right there.”

Bad River Reservation, Bad River watershed, and the Penokee Mountain ore body. Photo found on Indian Country Today

One of the main environmental challenges facing Bad River, that could pose a threat to their precious wild rice, is the world’s largest open pit taconite mine, which has been proposed to be located near the head waters of the Bad River. Taconite is a low grade iron ore, originally discarded as waste when higher grade iron was available. The Wisconsin state government passed legislation that would make it easier for the mine to go in, but it has faced stiff local opposition, and federal hang ups. For example, the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers said that they will not work with the Wisconsin state Department of Natural Resources on an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), one of the most important parts of getting a permit to mine,because differences in state and federal environmental requirements won’t allow the two governments to work together . The site of the proposed mine falls within the ceded territory that Ojibwe people have access to for traditional gathering, and so the Lac Courte Orielles (LCO) set up a Harvest Education and Learning Project camp, starting in April 2013, calling it a “living demonstration of treaty rights.”The camp was operated for a full year, with the county government then voting in March 2014 to evict the camp from the site. They moved to nearby private property to continue traditional harvesting and educational activities. For most recent updates on the mine, check the No Penokee Mine facebook site.

Tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins with a whitefish. Photo courtesy of GLIFWC

Tribal chairman Mike Higgins describes the Bad River tribe’s efforts to reject the mine, regain their land, and reclaim their food systems as part of a war. “It’s really finding wealth in a paradigm shift that is related to revolution. That is related to warfare, and related to the simple sweet premise of trying to take care of ourselves a live a good life.” But in describing warfare against mines that would destroy their environment, or tourists who have taken over land once used for rice camps and subsistence fishing, Mike is not describing violence and destruction, but rather the opposite. “war is actually about loving, living, taking care of each other in a way. And so anyway, when I say war, soldiers, I see the babies really equipped to understand their homeland, their love for their homeland and to be able to convey in beautiful ways why that’s important. So along that way, seeds, berries and squash and corn and deer and the ducks and wild rice, all of that stuff is going to be important.” The food systems projects at Bad River, from elders planting medicine gardens to youth learning how to harvest wild rice are all part of a vision to not only promote better physical but also cultural health.

4 comments ›