From April 14-16, indigenous food producers and chefs from all around the Great Lakes region gathered at the Oneida Nation conference center, and Tsyunhehkwa farm to discuss seed saving, exchange ideas around producer co-ops and techniques for improving soils, and to brainstorm ways of getting this amazing food onto the plates of community members.

The conference began with seeds and livestock workshops at Tsyunhehkwa farm, led by Rowen White (Mohawk) of Sierra Seeds Co-op, and Kyle Wisneski (Oneida) who is in charge of livestock at Tsyunhehkwa. Rowen gave a power point presentation about the importance of saving seeds, and some basics on plant breeding, as well as how to keep plants in the same species from inadvertently cross pollinating. Rowen also highlighted that “seed work is slow work.” and so it’s important to cultivate the next generation of seed savers. She encouraged participants to start by even adopting one heritage seed into their lives and gardens, becoming a “plant midwife,” stewarding life from the death of these plants each year. And then from there work to create and support community seed banks and seed initiatives, supporting seed keepers and regionally adapted crops (as opposed to “sweat shop seeds”, developed by large agri-businesses that have an exploitative relationship with the land)

Rowen and Zach Paige from the White Earth Land Recovery Project, teaching workshop participants how to select seed corn. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Dan Powless (Ojibway), food sovereignty coordinator for the Bad River Tribe, sorting through Oneida white corn. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Rowen dropping corn into the sheller, which instantly removes the kernels from the cob. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Ted Skennandore (Oneida), demonstrating winnowing corn, to blow away chaff from the kernels that will become food or be saved for seed. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Kyle Wisneski (Oneida), with a box full of day old chicks. They add a little honey to the water for their first drink, and then slide them under the brooder they’ve created to simulate the warm mother hen. Photo by Elizabeth

Happy grass-fed cows at the Tsyunhehkwa farm. During the last panel of the conference, we were served some really tasty summer sausage from these guys. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

For lunch Laura Manthe (Oneida) made the workshop participants a wonderful corn soup, and a mixed greens salad. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

After the workshops, we headed back to the conference center for an amazing meal by a panel of indigenous chefs. More on them in the next post.

Condolence ceremony to welcome all of the conference participants to Oneida. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Rowen White in one of her corn fields on her seed saving farm in northern California. Photo by Angelo Baca

In addition to hands on workshops, the conference offered two days of panels, offering Native communities the opportunity to showcase their projects and share their successes and challenges, and for regional soil, aquaculture, and grant writing experts to share some of their technical knowledge. The theme of seed saving was continued in the first break out session I attended, featuring Rowen White, along with Joy Hought from Native Seeds/SEARCH and Zach Paige from the White Earth Land Recovery Project. Rowen White is Mohawk from Akwesasne, but now lives in California where she runs a farm focused on seed saving, as well as the Sierra Seed Cooperative, a seed cooperative that pools seeds grown by northern California farmers for sale and distribution. The profit from the nearly 400 varieties they sell and distribute through a monthly seed CSA have gone to support growers, purchase tools to clean and process seeds, and provide scholarships for growers to attend conferences and seed schools. In addition she is a board member of Seed Savers Exchange, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving America’s heritage seeds.

Rowen described her path from discovering she was a “seedless person” who had come from a culture where seeds were so important, to 17 years later her responsibilities as someone who handles hundreds of varieties of heirloom seeds for a living. She spoke to the audience about how her great grandparents were part of the Six Nations ag society, taught by Cornell University how to grow food that was more civilized, straight row monocultures instead of the corn, beans and squash polycultures. But, as she described, traditional varieties persisted because there were far sighted elders who kept them growing in their gardens, even as they were told these were peasant food. Her work is looking to recognize the importance of the knowledge that indigenous people have held since the beginnings of agriculture, long before the Green Revolution, and to encourage people to build on that knowledge. “We’re all sprouts and seedlings in this movement” she told the audience. “Seeds and people are dynamic. We have co-creation with the seeds we steward.” This means preserving heritage varieties without insisting that they remain exactly the same. Rowen encouraged participants to “create heirlooms for the future” by selecting traits that are pleasing to the grower and that grow well on their farm. She described that for many of us, through colonization and acculturation, our food ways are tattered ways. with little bits of surviving wisdom. But “what I want to envision is that we’re survivors not victims.” Seed songs and the wisdom of elders survived. “Within the seed sovereignty movement we’re young and excited to reweave these shreds back together to create food systems in our values.”

Joy Hought works for Native Seeds/SEARCH, a nonprofit seed conservation program located in Tucson AZ, with a farm in Patagonia. Joy described that this seed collection is not just a collection of genes, but that each variety is precious as a whole organism connected to people in the American southwest and northern Mexico. The goal of NS/S is to couple the ex-situ conservation environment of the seed bank with programs that ensure in-situ access in local communities, back in the lives where they belong. The original seeds, most of which were collected 25-30 years ago, come from over 50 tribes and communities in the southwest and encompass many different agricultural and cultural traditions as well as climates and geological zones. The eventual goal of NSS is to support local indigenous communities in creating and maintaining their own seed banks. In the mean time, the organization distributes free seeds to indigenous gardeners, farmers and community groups in the southwest (last year they distributed enough seed to serve more than 500 individuals and groups), and works to support these recipients with educational materials. They also guard against inappropriate research use of the seeds that might lead to privatization. They are also working on curriculum for K-8th grades, providing materials for teachers to incorporate seeds into math, literacy, science, and horticultural standards. In addition, over the past six months Joy has been working on programs targeting Spanish speakers since 30% of urban youth in Tucson are Spanish speakers, many of them of indigenous descent, and Joy wants to make sure they can access the seeds of their people. Joy also travels around the country teaching seed education in an effort to help community leaders “regain these skills and lead their communities to seed sovereignty.”

Some of the 2,000 varieties of arid climate seeds that are curated by Native Seeds/SEARCH. Photo by Angelo Baca

Zach Paige has been working with the White Earth Land Recovery Project since 2012, when he also started attending seed school. Since then he has been working on creating a seed library working with White Earth Tribal and Community College and a youth garden program in the Naytawash community. Last year Zach worked with a number of indigenous community organization to write an Administration for Native Americans (ANA) grant to support seed education. Over the next three years, Zach will help organize twelve 2-day seed keeping workshops with all of the partner organizations in the Indigenous Seed Keepers Alliance, several of whom were in the room. As Rowen noted after Zach’s presentation, what she loves about projects like the seed keepers alliance and the ANA grant is that it “empowers us to create systems, seed banks and initiative by the people for the people for our own sense of self determination and sovereignty.”

The seed saving panel was followed by Jeff Metoxen (Oneida) of Tsyunhehkwa farm describing the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA). NAFSA founders and coordinators Pati Martinson and Terrie Bad Hand were also on hand to answer questions and encourage people to join.The intention of NAFSA is to support indigenous communities in restoring their food systems, in order to reclaim self-determination, wellness, culture, and their economies. NAFSA brings together individuals, communities, organizations and tribal governments to share and promote best practices and policies to enhance and create awareness around Native food systems.

Leslie Wheelock (Oneida). Photo courtesy of WXPR

The lunchtime keynote was Leslie Wheelock (Oneida), Director of the USDA Office of Tribal Relations, whose goal was to describe the various federal resources available to conference participants. Leslie described how the 2012 ag census identified 72,000 American Indian farms and ranches, although she thinks that’s undercounted by 50%. The average age of these farmers is over 50, and she’d like to lower that by bringing more young Native people into farming. She sees restoration as applying to land as well as youth. “How do we get youth back on the soil, interested in foods, teach them how to cook when people my own age don’t know how to cook? We never learned it.” She is heartened by the fact that “we have tribes and communities wtih kitchens, that have cooking demonstrations to help our people relearn how to cook our own food.” She described the Gila River community, which is located in a “food desert” and has some of the highest rates of diabetes in the world. Eighty years ago they were cut off from water, but they recently won a water rights settlement. Now they have land, they have water, and they want to grow food. Leslie has been working with them to establish community, school, and elder gardens, in part with funds from the farm to school program. She also connected them with NRCS (National Resource Conservation Services) to set up high tunnels to help extend the growing season. The Generation Indigenous Initiative focuses on youth and education, trying to restore the educational value to, and renovate, BIE (Bureau of Indian Education) schools. Leslie also pointed to Agroforestry, a department in the forest service of the USDA, which is designed to help people with cultivating forest spaces to grow wild foods like ginseng, mushrooms, berries, and medicinal herbs. Leslie is also working to remove barriers to utilizing traditional foods in schools and health care facilities. It turned out the USDA buying guide stated that these institutions couldn’t serve game. So now they’re working to take that out (hopefully by the end of April). The Wisconsin secretary of agriculture also invited federal, state and tribal people to talk about how to get traditional foods into food systems. They created a list of every potential barrier to this, and it was a long list (state laws were the primary barrier), but Leslie is encouraged that the conversation has begun. She concluded by directing participants to the USDA Know Your Farmer Website, which includes programs and services.

The afternoon included a great presentation by Paul DeMain (Oneida/Ojibway) and Jerry Jondreau (Ojibway) about the Inter-Tribal Maple Syrup Producers Cooperative, whose goal is to expand production of syrup by Native people by providing technical assistance, research on best forest management and production practices, and an entity to build and enhance communication and collaboration among tribal syrup producers and with outside institutions like the USDA. Paul DeMain is also known for his role in staving off the proposed GTAC mine we described in the post about Bad River, in part by starting the Harvest Education and Learning Project (HELP) camp on the site to draw attention to the sustainable natural resources available in the area that have been utilized by indigenous people for millennia. Paul describe these efforts in detail in a separate keynote presentation over lunch, in which he detailed the efforts GTAC went through to create the world’s largest open pit taconite mine on land that had been taken from Ojibway people, and how they maintained a presence on the land to draw attention to their treaty rights, and to the myriad other more sustainable uses for the land (pointing out that right now maple syrup is worth more per gallon than oil is per barrel). Describing the need for a maple sugar co-op, Paul detailed how in 1866 the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin produced over 75,000 pounds of maple sugar. Today native people are producing just a fraction of that. The acquisition of cane sugar in the Carribbean killed the maple industry (and was then overshadowed by beet sugar, and then corn syrup). But these replacement sugars have no nutritional qualities other than calories, where as maple sugar has 54 different vitamins, minerals and other compounds. When Paul first went to a Wisconsin maple producers meeting, and Amish guy said “it’s about time! This is your product!” The Inter-Tribal Maple Syrup Producers Cooperative was founded in an effort to create excitement among indigenous producers to pursue this product their ancestors were known for, as well as to create buying power for equipment and micro-loans for start up. Paul also discussed the need to rewrite codes and standards around syrup– light, clear, amber color syrup is labeled Grade A, but richer, smokier, kettle boiled maple syrup produced in a more traditional way (boiled, not reverse osmosis) is much darker. Paul also described the cultural importance in taking part in the maple sap harvest; “when the tree starts running and you take that first reinvigorating drink of the year, it tells you you lived all the way through a harsh winter.” He hopes that the co-op will bring people together and reinvigorate an industry “like heritage seeds being invigorated.”

Paul DeMain (Oneida/Ojibway) from Wisconsin and Jerry Jondreau (Ojibway) from Michigan presenting about indigenous maple sugar producers. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

Jerry is a tribal forester from Keweenaw Bay, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, which has the most dense sugar maple population in the world. He described how even though maple sugar was part of who the Ojibway were for a long time, in Michigan they are currently at .02% of what could be tapped. Jerry sees the production of maple syrup as a community building activity– this season they had babies from 5 months to elders 75 years old in the sugar bush. He sees maple sugaring as a healthy activity that will get people back into the woods, where they’ll discover the variety of other foods and medicines that still grow there. The co-op is an effort to support and encourage indigenous producers across tribes in the Great Lakes region, to utilized tribal and ceded territories in a productive, sustainable, and culturally constructive way.

Professor Patty Loew (Ojibway). Photo courtesy of NAJA

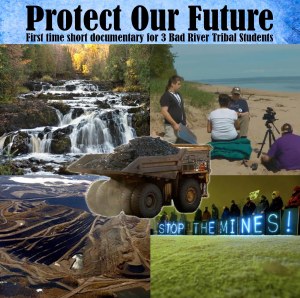

Wednesday evening’s keynote was delivered by Patty Loew (Bad River Ojibway), a professor in the department of Life Science Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a documentary producer, and a former broadcast journalist in public and commercial television. Patty described her methodology of media production through the Tribal Youth Media Initiative as “bottom up.” When she works with a reservation community, she first sits down with the elders and asks what they want their youth to learn, and who has the knowledge to teach the youth. Then she meets with the kids, and finds out what kind of media they want to learn– video, photography, music composition, webpage design, etc. Then she takes the learning concepts suggested by the elders and integrates that with the media selected by the youth. For her most recent project creating a documentary about the proposed GTAC mine that was threatening the Bad River tribe, the process was a little different. Patty described a sadness and resentment in the community over the feeling that they were not being heard in the process. There was only one public hearing in Madison 350 miles away, and people felt that the mining bill was a done deal before they even got there. The civil discourse over the bill was framed around jobs; there was never an opportunity for Bad River people to explain in any kind of public way waht the rice meant, how the mine would impact their lives and cultures. As one Republican legislator stated, “what’s the big deal, it’s just a bunch of weeds.” So during her 2013 sabbatical, Patty purchased a high definition camera package for the Bad River tribe and hired three 14 year old youth to create a documentary about the impact the mine would have on their tribe. The youth shot every frame themselves, wrote all of the narration, and composed original music for the documentary.

Poster by Michelle Danforth (Oneida) Posted at Sierra Club

The documentary highlights the cultural and ecological importance of the wetland that would be destroyed by the proposed mine. The community premiere of the film was in the Fall of 2013, after which it was submitted to regional film festivals. The film has won four major awards and was showcased as a centerpiece for a human rights film festival. The youth traveled with the film, presenting to audiences from 350 professors and grad students at one screening, to a group of youth on the Pima Maricopa reservation. The youth themselves have also been recognized for their media skills– non-Indian businesses in the neighboring town of Ashland have begun hiring the youth filmmakers to do videos and public service announcements for them. The project has provided skills to youth who can now stay on their reservation and earn a living. In other good news is that a few weeks ago, mine officials announced that they were abandoning the mine proposal. You can watch the 30 minute film “Protect our Future” here.

In addition to several other wonderful presentations ( I could only make it to so many panels! Check out the full agenda) another that stood out for me was Amber Marlow’s presentation on the food systems development at Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibway Community College (LCOOCC). The College has a 220 acre farm, 75 acres of which are tillable. The goal is to utilize this land to provide access and resources to community members. They are also working on alternative energy, utilizing biomass, geothermal, wind turbines and solar with the eventual goal of being off the grid. Todd Brier described the college’s aquaponics demonstration project, which provides hands on experience for college students, community members and K-12 students. The system grows basil, tomatoes, peppers, and spinach utilizing the nutrients from the fish waste.

Clean up day at the LCOOCC farm. Photo courtesy of LCOOCC

The program also operates a seed library, in a climate controlled portion of a barn that is kept at 42 degrees. In looking at census data, Amber noted that there are 231 farms in Sawyer County, but only 2.6% of them are native operated. Recognizing the need to attract community members to grow their own food, LCOOCC developed a beginner producer program. The first year they recruited 10 families to the program, and 18 are currently signed up for this year (in addition to the first year participants, who will be taking part in a year 2 curriculum). The program involves twice monthly workshops which involve the entire family– they cook a meal together and are provided with seeds, tools, a canning book, and a water bath canner. Upon the successful completion of the program, the family receives a stipend (it was $750 last year, and $500 this year). This year the year 2 group will also be taking master gardening classes and will mentor the new families as part of their 26 hours of community service. Upon the completion of the program the first year, participants were given an evaluation form– 100% said they would keep gardening, and 33% said that starting a co-op would motivate them to sell extra produce. Through funding from the First Nations Development Institute and USDA Socially Disadvantaged Farmers/Ranchers/Veterans, LCOOCC has been developing a commercial kitchen that allows participants to do post-harvest processing on the farm. Two days a week they can sell their produce to the farm, and the farm markets it under one label to their little retail outlet. They are now working to increase retail outlets, and get more produce into the casino and local grocery stores.

The Great Lakes Intertribal Food Summit was a great opportunity for Native food producers to share knowledge, exchange seeds, and make the necessary connections to not only strengthen their individual and community operations, but also the broader Native food movement.

3 comments ›