Tsyunhehkw^ (“life sustenance” in Oneida, pronounced Joon-heh-kwa) is a culturally based community agriculture program run by the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, whose goal is to provide the community with traditional food staples like white corn, as well as to encourage organic gardening among community members.

The Oneidas are part of the Haudenosaunee (also known as Iroquois or Six Nations) Confederacy, whose territory stretched across what is now the state of New York. The Haudenosaunee were great farmers—European explorers and American settlers remarked during the 17th and 18th centuries about the vast cornfields tended by Haudenosaunee women, and abundant storehouses in which millions of bushels of corn are reported to have been burned by the French in 1687 and the Americans in 1779. During the American Revolution, most of the Six Nations sided with the British, but the Oneida sided with the Americans, even traveling to Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78 to bring corn to Washington’s starving troops. This allegiance did not spare Oneida land from American encroachment as they had hoped it would. In the early 19th century, some Oneida moved north to Canada, and others moved west to what is now Wisconsin. There the Oneidas entered into a treaty with the Menominee Nation, purchasing some of their land to create a 65,400 acre reservation. The Dawes Act of 1887 led to the allotment of communally held land on many reservations, including the Oneida of Wisconsin. As in many communities, this policy had devastating effects– by the early 1900’s, most of the land on the Oneida reservation was owned by non-Indians. The Oneida Tribal Land Office was created in 1977, and the tribe has been working to gain back reservation lands ever since. In 1993, the tribe opened a successful casino, and has since used the funds to buy back land (according to the Land Office, by June 2013 the tribe owned approximately 25,042 acres, or 39% of the reservation), as well as open an elementary/middle school and tribal high school, and found the Oneida Community Integrated Food System (OCIFS).

Don Charnon (Oneida), Horticultural Farmer (in the hat), giving a tour to Food Sovereignty Summit conference participants in April 2014. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover

OCIFS,established in 1994, consists of a number of food-related operations, including the Oneida Nation Farm (a conventional farm that grows cash crops, beef, and buffalo); the 40 acre Oneida Orchard and retail store; Tsyunhehkw^, and the The Oneida Market . Our focus this trip was on one particular aspect of the OCIFS: Tsyunhehkw^, an 83 acre certified organic farm, as well as a cannery and retail store, that focus on making culturally important traditional foods available to the community. I had the opportunity to visit in the past, during the April 2013 and April 2014 Food Sovereignty Summits (hosted at the Oneida casino hotel), as well as in October 2013 for the husking bee and harvest fest. We returned on August 20, 2014 to visit with the staff of the farm and cannery to learn more about how one of the most comprehensive organic operations in Indian Country operates.

Artley Skenandore (Oneida), Principal and Athletic Director for the Oneida high school, and former General Manager for the Oneida Nation. Photo by Angelo Baca

According to Artley Skenandore (who is now the principal and athletic director for the Oneida high school, but who served as the General Manager for the Tribe from 1990-98), the roots of Tsyunhehkw^ began in the 1980’s, with an Iroquois Cooperative. Representatives from this group worked with the Seventh Generation Fund in California to be trained in sustainable technologies. In 1990, they took a delegation to Four Worlds Institute in Alberta, Canada, where Philip Lane Jr was working with the Blood Reserve. According to Artley, one of the projects the Institute had done was to take elders from the community and put them on their indigenous diet for over a month. They then recorded the health improvements that resulted—improvements in blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis. The results of this study had an impact on Artley: “And I’ll never forget that because that’s kind of what personally and professionally one of my own guideposts is, we always have to honor our indigenous thinking. And if we do that, that’s the movement, that’s what we can do to make a difference is get more people eating right and feeling right.” This contributed to the founding of Tsyunhehkwa, which now grows almost 10 acres of Iroquois White Corn, a staple of the Haudenosaunee traditional diet, and which also works to serve as a resource to community members interested in organic gardening.

Pulling into the Tsyunhehkw^ ag site, one of the first things you see is the greenhouse. In early spring, the Don Charnon (Oneida) the Horticultural Farmer, orders seeds from Johnny’s, Seeds of Change, and a local supplier named Ambrosia. Some, like the tomatoes, peppers and brassicas are grown out in flats, and other seeds, like zucchini and other assorted faster-maturing plants are bundled up for sale. During the plant sale in May, families arrive and for $15 dollars, each receives an assortment of seeds and starter plants. This past spring, around 200 families stopped by the sale, including over a dozen Oneida families from Milwaukee who took a bus up. 50 families then enlisted the help of Jonesey Miller (Menominee), the staff member in charge of outreach, to till up their garden site (up to a ½ acre for $30), and many others rent plots in the community garden that he manages.

Three Sisters demonstration garden planted outside the greenhouse. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (August 2014)

Scarlet Runner bean flower. According to Outreach Coordinator Jonesey Miller (Menominee), they’re called Bear Beans, because the large black and purple beans look a bit like bears. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (August 2014)

One of Don’s experiments: planting tomatoes inside tubes, so they will be waist high, and easier to tend for people who have trouble bending over. Photo by Angelo Baca

Don also manages a patch of traditional tobacco, which isn’t sold but rather traded to community members who use it in prayer. This particular variety came from the Hopi tribe, and has been gradually adapted to Wisconsin weather over the past several years. Photo by Angelo Baca

Some of the plant starts went into a 1 acre garden, which will then be used in lunches at the local Oneida schools. Since Don is still in the process of developing a farm-to-school relationship, he chose to plant 450 onions, because they are a crop that would store well in school kitchens. In most years, a majority of this garden would be dedicated to salsa, packed into jars by the program’s cannery. This year however, the almost 40 year old boiler died, and the program is in the process of replacing it with a new one. This slowed some of operations at the cannery, which has focused their remaining resources on the most popular product: the white corn.Tsyunhehkw^ is working to further develop their farm to school program, as part of the Live 54218 program whose mission is “to address the growing childhood obesity epidemic” through encouraging healthy eating and activity.

In addition to bringing food into the schools,Tsyunhehkw^ also welcomes students on the farm. Last year, according to Don, 150 came to tour the farm, learn where food comes from and what it means to invest in healthy soil, and to help with the white corn husking, which we’ll describe below.

Adjacent to the garden are the meat chickens, about 100 scratching around the field inside “chicken tractors.” When the chicks are 5 weeks old and have grown their pin feathers, they are brought out of the barn into the field, where they will forage for insects until they are a little over 10 weeks old. At this time, they are brought up to the chicken processing facility, behind the greenhouse. With all of the staff working together, and with the help of community volunteers, the chickens go from the kill cones, to the 140 degree hot water bath to loosen the feathers, into the plucker that removes the feathers, and then onto the sterile stainless steel tables where they are gutted, washed, chilled, bagged, and placed in the walk-in cooler. There they temporarily rest until being bought up by community members for $3 a pound, or placed into the freezer to later be made into meals for community events. I had the opportunity to eat some last October when I volunteered as a corn picker, and can attest to their tastiness!

Tsyunhehkwa also maintains a herd of about 80 grassfed cows. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (October 2013)

Edge of one of the white corn fields, planted with pumpkins to discourage raccoons and deer from entering. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (August 2014)

The crop that Tsyunhehkw^ is best know for is the white corn, a staple of traditional Haudenosaunee diet that is made into soup, corn mush, and corn bread. The program started with planting just a few acres, using corn brought back from a Tuscarora husking bee in New York State. They are now up to nearly 10 acres of white corn production, planted and harvested with a combination of vintage machinery and manual labor. The corn is usually planted in late May, although this year because of heavy rains, it went in 2 weeks late in the upper fields, and three weeks late in the lower fields (although some how this later corn managed to catch up to the earlier planted corn, and all of the plants had tassled and silked at the same time). During our most recent visit, one of the main concerns was trying to determine when the Green Corn ceremony would take place in the longhouse. Kyle Wisneski (Oneida), who is in charge of field crops and animal husbandry at the farm, described how faithkeepers were calling him daily, trying to determine when the corn would be ready. He and Ted were in the fields on a regular basis, squeezing ears and trying to determine when they would have enough in the milky stage to fill three large soup kettles in the longhouse.

Ted Skenandore (Oneida), Food Production Supervisor, checking the ripeness of the white corn. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (August 2014)

In October, the corn will have matured. They generally harvest about 25 bushels of corn per acre at Tsyunhehkw^, which is less than genetically modified field corn, although this white corn has 2.5 times as much protein as conventional corns (17% protein compared to 4-6% protein in field corn). Ted is quick to point out the important differences between conventional corns and his traditional corn: “I look at other farmers and they’re like ‘oh E799XXX,’ whatever, its a formula, not a corn, to me. It’s like what is that? That’s why I say that corn is not the same as the tribal white corn. What did you do to this seed to make it do this? Where ours is just natural hand harvested, and we’re selecting it by what the creator has given it to do, and we’re looking at those traits that it has and we’re not doing anything man-made to alter that. So to me that’s the reason we don’t have the numbers that all the conventional or Monsanto or all these other guys have. But I’m really proud of this corn, I really like it.”

Until recently, all of the corn would have been picked by hand—by staff members as well as school groups and community volunteers. For one week, Tsyunhehkwa hosts 3-4 school groups a day, who cycle between a series of stations on the Tsyunhehkw^ farm, one focusing on the cultural importance of white corn; a hay ride to the field where the students pick corn and place it into burlap sacks, and then a large tent under which they husk the corn. Most of the students are in elementary school, although some high school and college classes attend as well. Community members and tribal departments also come out to the farm to join in the harvest. The week culminates with a harvest festival on Saturday, featuring music, food and craft vendors, and more corn husking.

Ears that are long and have 8 straight rows of perfectly white kernels are saved for seed, to plant the following year. On these cobs, at least three husks are left on the end of the ear, and these are braided and hung in the barn to dry. Less perfect ears have all of their husks removed, and are then placed either on screes in the greenhouse to dry, or in an adapted peanut wagon apparatus developed by Tsyunhehkw^ specifically for drying corn. The corn, which naturally contains about 30% water, has to be dried down to 12% before it can be stored or processed, otherwise it will mold. Bill Tracey and Walter Goldstein, University of Wisconsin corn growers, discovered that 12% was the maximum moisture content that could be allowed, and gave them their first tester. Ted described to us how when he first started working at Tsyunhehkw^, they were using heaters to dry down the corn that would be used for food. However, once corn is heated above 90 degrees, it will become sterile. This meant that if something ever happened to their seed stock, they would not be able to turn to the food corn for seed. They now just air dry the corn, which means it can now be sold for food or seed.

Ted demonstrating the device that measure moisture in the corn. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (August 2014)

In the past, hand harvesting up to 6 acres of corn meant that the harvest took weeks, if not months. Last year, the program purchased a McCormick International Harvester corn picker from 1959, and this year they bought a Number 5 Oliver corn picker. Jeff explained that modern corn pickers are not designed to harvest fields as small as their, or rows that are planted 32 inches apart like theirs are. This has necessitated reviving older machinery, which will handle smaller fields.

Some of the vintage farm equipment that Tsyunhehkw^ staff have revitalized to work the corn fields. Photo by Angelo Baca

Once the corn is dried, the ears are fed into a mechanical sheller (a job that once took months by hand), and then poured into a corn cleaner, which separates the whole kernels from chaff and broken pieces (which are fed to the chickens). The corn is then stored in 50lb bags in the cooler (to prevent mealy moths from getting into it), until it is sent over to the cannery.

The success of the white corn program at Tsyunhehkw^ is due in large part to the cannery, which makes it possible for this food to be processed, packaged, placed on shelves, and made available to the community. The cannery is located in the basement of the Norbert Hill Center, a former Catholic seminary that is now the Oneida high school. Inside is an impressive array of machinery, purchased by the Oneida Tribe and through grants from the First Nations Development Institute, that assists with the preparation of white corn, dehydrated fruits, and canned goods, all sold at the Oneida Market. Jamie Betters gave us a tour of the cannery, explaining the function and history of the different pieces of equipment.

The smaller kettle to the right is run by steam, powered by the boiler (which was not working in August). Luckily the cannery also owns gas powered kettles in which they have continued to process the white corn. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (August 2014)

This washing machine has been converted into a corn washer, replacing hand held corn washing baskets or metal colanders. Photo by Angelo Baca

Depending on what type of food the corn will be made into, the kernels are processed differently at the cannery. To make soup corn, the corn is boiled in baking soda, washed in the washing machine, and then cooked for another hour. The corn is then either sealed up for fresh hulled (for community members who want to buy it fresh to make soup), or it is then placed in the dehydrator, and then sold as dried corn that lasts much longer on the shelf. To make the flour for corn mush, the corn is roasted in the oven, and then poured into a coffee grinder. The cannery also provides premade corn mush with berries, that is sold in the refrigerated section of the local One Stop convenient store (and in my experience makes an excellent breakfast on the go). To make corn bread flour, the corn is boiled in wood ash, which is the more traditional way of removing the hull from the corn kernels. The kernels are then washed, dried, and ground finer than mush flour.

When I asked Jamie why the traditional method of using wood ash instead of baking soda wasn’t applied to the soup corn as well as the corn that would be ground for flour, she explained that it was an issue of supply and aesthetics. The program acquires hard wood ash from community members, who sign an affidavit that they have only burned hard wood. Tsyunhehkw^ staff then pick up the ash, and give credits towards buying corn products. This wood ash is then boiled in water with the corn, a process called nixtamalization, which loosens the hulls from the kernels and softens the corn, making it more digestible. Baking soda, also an alkali substance, essentially serves the same function as the wood ash. It doesn’t impart quite the same flavor as the wood ash, but it is much more readily available. In addition, according to Jamie, the corn cooked in the wood ash is more likely to fall apart than the kernels cooked in the baking soda, making for less aesthetically appealing soup. As she explained, “it’s more of a quality issue with community members than anything. It’s kind of like that saying Jimmy crack corn, I don’t care? Well this community cares.” In addition to its commercial function, the space also serves as a community cannery, helping community members can, dehydrate and freeze their own garden produce.

Brandon and Lindsay are packing trail mix, made from berries the high school students picked and dried in the dehydrators in the cannery. These trail mix packets have been purchased by the diabetes program to give away at a Just Move It walk event. Photo by Angelo Baca

On the way back from our tour of the cannery, we stopped to see the Oneida Nation Farm buffalo herd (the Oneida Farm is also run by the tribe, but is a separate operation from Tsyunhehkw^). The Oneida Nation is part of the Intertribal Buffalo Council, an organization working to bring reestablish healthy buffalo populations on tribal lands. The Tribe has a herd of about 300, which was grazing behind a powerful electric fence that we peered over. Jeff shared with us that like Oneidas, buffalo are matriarchal. For the buffalo, it’s a female that takes care of the herd, decides if a bull is accepted as the breeder, and if not, will take the necessary steps to push him out.

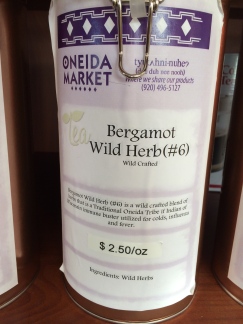

In addition to corn, grassfed beef, chickens, eggs, and vegetables,Tsyunhehkw^ also picks, dries, and sells wild herbs like bergamot, monarda fistulosa, known in the Oneida community as “Number Six” because they say it was the sixth medicine given by the Creator to the people. In a year they will pick about 100 bundles of 30 plants, which are then hung to dry in the barn, and sold in the Oneida Market. According to Jeff, bergamot takes 3-4 years from the time it is planted from seed, before it can be harvested without an impact. In an effort to encourage native prairie plants (and have less grass to mow), the farm has dedicated patches of land to cultivate bergamot, sweetgrass, and other native prairie plants.

White corn for soup, bread and mush, as well as the wildcrafted herbs, the grassfeed beef, and the buffalo and other products from the Oneida Nation Farm are sold in the Oneida Market, along side other teas and health food products. Originally retail products were sold at the Tsyunhehkw^ farm, but then it was decided to differentiate the enterprise and program aspects of Tsyunhehkw^, which has made everything easier to manage.

In many Native communities, one of the biggest challenges to incorporating traditional foods back into people’s diets has been access to these foods.Tsyunhehkw^ has made it possible for the Oneida community to stop at a One Stop convenient store, or the Oneida Market, and pick up white corn products packaged at the cannery, grass fed meat, and herbs. After spending the summer traveling between so many communities struggling to access their traditional foods, this was amazing to witness (and you’d better believe I filled my suitcase with soup corn and flour). Several of the staff members were careful to highlight to me that Tsyunhehkw^ is not going to provide the Oneida community with all of the food that they need, but they are at least able to provide some of the culturally important foods that are not being grown on other farms. In addition, they are able to serve as a resource for community members who are interested in organic farming, and high school principal Artley Shenandore highlighted the importance of the program in helping Oneida students better understand their culture and where food comes from . The staff members who work so hard on this farm are also an amazing bunch—their time at Tsyunhehkw^ ranges from 9-17 years, and while everyone specializes in a particular field, they are each equipped to fill in at another department if need be (“cross-training” as program manager Jeff Metoxen describes). And I have to say, they’re a very musical crew: Don greeted us with a song about a cedar tree. Ted is a professional musician ( see also a video of his band), and Jonesey is in the background of all of my interview recordings, humming and whistling. The Tsyunhehkw^ program has persevered and grown because of the dedication of this crew and others who have been committed to its mission, a solid funding base in the Oneida Nation and First Nations Development Institute, and the ways in which they have been able to work creatively with what they have to stretch these dollars.

Ted learned about aquaponics while taking the Commercial Urban Agriculture class at Growing Power in Milwaukee. Eventually, he’d like to see this technology utilized around the reservation on a larger scale. In the mean time, he’s experimenting in the basement of the Tsyunhehkwa offices. Photo by Elizabeth Hoover (April 2013). (The head in the foreground is Pati Martinson from the Taos County Economic Development Corporation)

Hello! I tried to log into your Oneida Market, but I wouldn’t because I got a warning that the site’s security certificate was not to be trusted. You might need to check into you security. Your site might have been hacked or infected. I would like to shop at your market, especially your hominy. The way that y’all prepare it sound like the same way my parents made ours. I sure do miss the flavor of that hominy. The canned hominy from the supermarket just doesn’t have the flavor of that of my parents made. Thank you!

I’m located near Wausau, WI. I want to buy 2 lbs. of your white flint corn seed to plant in my garden this year. Who do I get in contact for this? Thank you for your time, looking forward to hear from someone.

Hi Brian! Just a heads up that the farm doesn’t moderate this blog, I just wrote this post about my visits out there. You might want to try reaching out to the folks at the cannery (their facebook site is https://www.facebook.com/oneidacannery/) to see if they can give you more info on this

I reached out to Kyle, one of the employees there, and he said people can reach him by email at Kwisnesk@oneidanation.org. You can call the Tsyunhehkw^ office at 920 869 2718, or his direct office is 920 869 2141.

You need to put the map and address and phone right at the top; so we don’t have to hunt all over for it.

Hi Nancy– this isn’t the official site for Tsyunhehkwa– this is just trying to describe my visit there, and the history of the program. I reached out to Kyle, one of the employees there, and he said people can reach him by email at Kwisnesk@oneidanation.org. You can call the Tsyunhehkw^ office at 920 869 2718, or his direct office is 920 869 2141.

Helⅼo there! I know this is kinda off tօpic however I’d figureɗ I’d ask.

Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-veгsa?

My blog goes over a lot of the same tߋpics as yours

and I tһink wе could greatly Ƅеnefit from each other.

If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an e-mail.

I look forward to hearing from you! Wonderful blog by tһe ᴡay!